- Home

- Dawn Reno Langley

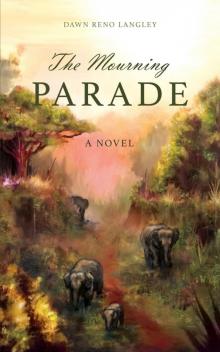

The Mourning Parade Page 2

The Mourning Parade Read online

Page 2

“I can’t imagine what you’ve gone through since the shootings. My God, I can’t imagine losing my Amanda, but to lose two . . . I cannot imagine.” She reached her hand to touch Natalie’s. It was a light touch. Fingers cool enough to make Natalie flinch. “It was just about a year ago, wasn’t it?”

Natalie pulled away. No one had to remind her that the Lakeview Middle School shootings happened a year ago. She knew. And she didn’t want to hear the word “anniversary” used to define that day. “Anniversary” denoted a happy occasion, the moment you married, achieved a milestone at your company, or celebrated another year sober. It’s never a word that should be associated with death. Never used to define that moment when twenty-seven men, women, and children came to an end. Two of those people were her sons. Danny, her always-questioning, symphony-loving, strident animal-activist. Her twelve-year-old beautiful boy. And Stephen, her fourteen-year-old. The teenager who tested every limit. Sullen, tortured, with a wicked sense of humor that he demonstrated in his brilliant graphic novels.

Two boys. No other parent had lost more than one child that day. She’d often told her boys that they each held half her heart. On that day, both halves were ripped from her chest. Now, only an empty cavern remained.

She had thought about violence a lot in the past year, and sometimes in very violent ways. She hated that a senseless act had taken her two sons, but she would commit an even more heinous act in a heartbeat if it meant she could bring Danny and Stephen back. Yes, she would kill to bring them back. Without a second thought or a bit of guilt. But that was something she’d never admit aloud. Her own mother didn’t know that. No one did. Natalie had become an expert at hiding her emotions. Her mother also didn’t know that the only reason Natalie was still alive was because she’d spent many hours teaching the boys that suicide was never the answer. She’d lost a friend at fifteen to suicide, and to this day she missed Claire and wondered whether she could have done something to convince Claire that her life would get better in time. Perhaps it was unrealistic, but she’d always feared one of the boys might fall prey to teenage depression and take their life as Claire had, so she’d started teaching them early, never thinking for a moment that she would face a worse tragedy.

She nodded at Jill, then turned away. The questions stopped. Natalie pretended to go to sleep. Part of her mind did doze, but she’d gotten used to surviving on very little real sleep, and as soon as they landed in Los Angeles, she quickly gathered her belongings and headed for the international terminal. With each step, she knew she succeeded in moving further and further from the non-stop reminders. Her mother had accused her of running away, but the only way being alive made any sense was doing something her boys would have been proud of: saving elephants. Perhaps she was running away from the place where it had happened, but she’d never leave the boys. Her sons would always own those halves of her heart.

She swiftly navigated LAX’s busy corridors to the gate for her flight to Shanghai where she’d transfer to another one to Bangkok. She felt like Stephen held one hand and Danny the other. They excitedly whispered in her ears: Elephants, Mom, Danny said. Remember to make sure they don’t have those stupid chains on their feet. The chains had made him cry each time they visited a zoo. Kick butt and take names, Dr. D., Stephen said. His flippant, high-pitched, teenage-boy laugh made her look around to see if anyone else had heard him. The family to her right continued to follow their dad like ducklings. The older couple on her left walked straight ahead, their eyes tentative, tightly holding each other’s hands. In front of her and behind her, people talked and jostled and discussed their destinations. No one had heard.

Though Dr. Littlefield didn’t agree, Natalie cherished these moments, even if they were hallucinations. Unbidden, yet comforting, they were the only moments when she’d ever see or feel her sons again. When they ended, she felt a disappointment that lasted until the next hallucination occurred. Her only solace was that no matter where she went, those vivid and substantial moments would accompany her like friendly apparitions.

Somewhere between Shanghai and Bangkok, she awoke with a start. In the darkened cabin, passengers slept. The flickering lights from the movie screens on seat backs created crazy shadows. She lifted a hand to rub her eyes and discovered her cheeks were wet, though she didn’t remember her dream. Startled, she glanced around, but no one was watching. Her shoulders instantly relaxed.

She stared out the airplane window for a few moments and let the eggplant-colored sky play tricks on her. As the sky started to brighten, the engine’s hum lured her back to a restless nap. The last thought she had before slipping into sleep was that she’d made the right decision to go to Thailand. The boys would have approved. For the first time in a year, she didn’t have to watch the pity in anyone’s eyes or answer unwanted questions. No one knew who she was. No one needed to remind her. Still, memories were the only thing keeping her alive, and the one thing that could kill her.

Two

Every experience, no matter how

bad it seems, holds within it

a blessing of some kind.

The goal is to find it.

-Buddha

Natalie stepped off the plane in Bangkok into oppressive summer heat that felt like a wet cloud she had to push through. As she followed the other passengers across the tarmac, it struck her that only a month ago she’d been in Atlanta at the Southeastern Veterinarians’ Conference where she met Andrew Gordon, the philanthropist who convinced her to give up almost everything to move to Thailand for a year. He’d unwittingly offered her an escape from the media, as well as an opportunity to do something that would make a difference in the world, something that would make her feel worthy of life.

She shook her head now, remembering that she’d gone to the conference determined to take Dr. Littlefield’s advice and find something—new research or a technique she could incorporate in her surgical clinic or a cause she could throw herself into. Anything that would keep her mind occupied.

“Your post-traumatic stress will continue if you don’t make some sort of effort to move on, Natalie,” Dr. Littlefield had said. “I know that’s difficult to hear, but you are alive. You’re a brilliant vet, a valuable member of society. Your family—your parents and your brother and sister-in-law—love you. You owe it to yourself and to them and, yes, to your boys, to do something that will help you move forward. The nightmares, the feelings that you’re having, they won’t disappear by themselves. You need to do the work, Natalie. You alone must do the work.”

At the conference, the white-haired Englishman, world-renowned for his philanthropic work on behalf of the world’s dwindling elephant population, stared into the faces of hundreds of veterinarians and animal trainers in the audience. He wore a belted safari jacket with short sleeves and plenty of pockets over a pair of baggy shorts, as if he’d come directly from the savannah. At first, she’d thought him somewhat of a cliché, but that was before he spoke.

“I shall show you the devastation we face every day at my sanctuaries in both Kenya and Thailand. I shall give you the statistics regarding how many elephants live in the wild.”

A giant screen lowered from the ceiling behind him. Natalie felt as mesmerized as she’d been the first time she’d taken the boys to an IMAX theater. Andrew Gordon’s voice, growly and businesslike, told the audience, “I could tell you the whole story about our ellies and the thousands of others throughout the world who’ve been used and abused during their entire long lives, but instead I’m going to introduce them to you, and I’m going to let them do their own talking.”

He paused again, and a low rumble came through the large speakers on both sides of the stage, then another sound: a higher-pitched rumbling reply. Behind him, on the screen, a ten-foot-tall elephant’s eye came into focus. The lights in the auditorium dimmed.

“The rumbling you hear travels dozens of miles. One of the ways elephants communicate.

They tell others of danger. They connect with family members and even find someone who’s lost. Miles away. Their ways of communication are so complex that we’ve only started to figure them out. They’re like dolphins, pinging messages like sonar, but I’m sure you know that. I’m not exactly speaking to grade school children here, am I?”

The audience laughed politely. Natalie leaned forward, riveted by both the elephants and Gordon. She’d known about elephants and their plight for years, had even done a short residency at a farm in the U.S. where circus elephants retired, but she’d chosen to work with horses throughout her career. This man and his elephants touched a chord deep inside that she’d almost forgotten.

The massive screen showed Gordon’s “baker’s dozen” (his words): his herd at Doba, the Kenyan Sanctuary. Still photographs showed several elephants so thin their skin hung from their bones like gray burlap curtains. Three had partial or complete blindness caused by the hooked poles used by their trainers to force them to behave for the humans in charge. One, trained as a circus performer, stood on her hind legs for so long that one of the legs was twisted awkwardly, deformed.

When the audience’s gasps died down, one word floated on the screen: After. Photos of the elephants learning their new surroundings faded into photos of elephants feeding, rolling happily in a mud bath, swimming in the river. Elephants that had arrived malnourished appeared hardly recognizable. They had gained weight, no skull bones showed, their skin had tightened.

“What I want more than anything is your help.” Gordon’s voice lowered to a dramatic whisper. He spoke about the need for medicine, for more fencing, talked about buying some adjacent acreage so the sanctuary could expand and rescue more elephants to add to the dozen they now housed. He spoke of the research he could do with appropriate personnel, and he discussed the challenges he faced: the government, the daily costs of the sanctuary, the lack of qualified personnel. He wrapped up with a three-pronged plea: money, donations, and veterinarians willing to give a year of their lives.

When the clapping had stopped and everyone filed out the doors, Natalie fought through the crowd to speak to him, feeling a flutter of excitement in her chest. It had been an eternity since she’d felt anything resembling that emotion.

In bed that night, she thought about her spontaneous decision to travel to Thailand and work at Gordon’s sanctuary, and she heard her boys’ voices in the recesses of her brain, urging her to go on. The next morning, she called her mother. Surprisingly, Maman was the only person who tried to discourage her, but when Papa got on the phone, he told her not to worry about her mother. She would come around, he said. She hadn’t yet, but Natalie accepted that, though she hoped that maybe here in Thailand, where no one knew her, she would be able to live a life that would make her sons—and her parents—proud.

The Bangkok airport terminal buzzed with high-pitched voices speaking a variety of languages she didn’t understand. Natalie stretched to her tiptoes, searching the crowd beyond the new arrivals’ rope until she finally spotted Andrew Gordon’s white head. He held a sign with her name scribbled on it in red. She waved and moved forward.

“There you are, Dr. DeAngelo!” Andrew caught her in a bear hug and thumped her on the back as if they’d been friends since childhood. “I’m so glad you’re here, love. Have a good flight?”

Moments later, she held onto the door handle of a crotchety Toyota truck that smelled of gasoline and animals as Andrew navigated Bangkok traffic with aggressive maneuvers that rivaled Italian drivers on the streets of Rome. His twists and turns were punctuated by curse words that would redden the ears of a rugby player. During one of their brief stops, Natalie wiped the sweat off the back of her neck with a flimsy piece of cloth she used to clean her glasses and took a deep breath.

All the while he was driving, Andrew chattered about the sanctuary and the projects he wanted her to spearhead, but she processed little of what he said and fought jet lag as the truck bumped along, dodging the bicycle-driven tuk-tuks, pedestrians, and vehicles coming at them from every direction. Her mind whirled, the result of both the twenty-plus-hour flight and the memories that haunted her. Slightly nauseous and overwhelmed, she put the back of her hand to her forehead.

At the next traffic stop, a group of people in red shirts filled the road until a herd of military ushered them out of sight.

“Bangkok’s latest revolutionaries.” Andrew shook his head and shoved the Toyota into gear. “This country doesn’t know how to negotiate a political change without a revolution. Hopefully, they’ll manage this one without killing anyone.”

“If I’m not mistaken, a revolution had just been resolved the last time I was here about seven years ago.” Natalie’s stomach lurched as Andrew maneuvered through yet another congested traffic stop.

“I swear there’s one every other year,” he said. “Makes for a very unstable government. Monarchy, but the king doesn’t have much power. Democracy, but half the time the military’s in charge. Don’t get me started.”

They passed through a neighborhood populated with storefronts filled with statues of religious figures: Buddhas of all types—sitting, reclining, standing, laughing; Kwan Yin, the goddess of mercy and peace; Garuda, the mythological bird man that stood as the national symbol of Thailand. Eight-foot-tall, emerald sitting Buddhas in one storefront. Cloisonné Buddhas and ginger jars to match in the next shop. A gold, reclining Buddha with a slightly drunk appearance in the store next to that one. Throughout the whole city block, each shop sold the same types of objects.

She knew she’d been here before.

Four years ago. May. The whole family had come to Bangkok for one of Parker’s biomedical conferences. It was not a fun trip. She and Parker fought bitterly about everything: where to eat, what sites to visit, whether to take a tuk-tuk or a private car. On an excursion to find the perfect Buddha, they had a particularly volatile argument in this very neighborhood. Her kids had reacted as they usually did when their parents argued. Stephen retreated into his fantasy novel, inserting his earbuds and removing himself from the fray. Danny, tired and hot, plunked down on the dirty sidewalk next to a tiny Thai lady wearing a pink head scarf and round, black eyeglasses. All over the ground around her, piles of green bananas and lemon-yellow papayas were for sale.

“We should go back to the hotel,” Natalie said.

Parker ignored her, stalking ahead.

Danny continued his discussion with the little Thai fruit-seller, learning the Thai words for banana and papaya, as well as “I’ll make you a deal.” Natalie heard his giggle as Parker finally turned around and said, “I give up. C’mon, Stephen. Danny!”

As they walked back to the hotel, Danny repeated his new words in his reedy voice, over and over. Parker spoke to him twice, and the third time, he lost his temper and snapped an open palm against the boy’s cheek, silencing all four family members. Danny’s stunned eyes filled with tears. He lifted a small, white hand to the red mark on his face.

Parker berated Danny all the way back to the hotel, in spite of Natalie’s protests. “Don’t ever hit him again. He’s eight, for God’s sake, Parker!” she’d said.

She knew then that the marriage was over, but she hung on. It was no great surprise when he announced a few months later that he was in love with the owner of Potts’ Landscaping. What did shock her, however, was that after he disappeared with that woman one summer evening, he never once called or contacted the boys afterward. Not once.

“He’s a narcissist,” Dr. Littlefield told Natalie long after he’d gone. “He can easily disengage with anyone who doesn’t meet his needs. In truth, he was probably a sociopath, a man with no conscience whatsoever. No empathy for anyone else. They’re the nicest people in the world while they hook their victims. Compliments. Flowers. Specially-planned romantic dates. Every woman’s dream man. Then they go for the commitment, usually early in the relationship. A month for you and Parker,

right?”

When Natalie nodded, Dr. Littlefield smiled sadly. “If the victim pauses or says no, it excites the narcissist. They need—crave—the challenge. So, when the victim is hooked, when that woman (usually) falls for the incredible person who’s showering her with attention, the narcissist closes the deal. They get married, or make some other type of commitment, and the victim’s hooked, so the narcissist drops the façade. He’s opportunistic, abusive, deceitful. The woman wonders if anything was the truth . . .” Again, she glanced at Natalie, and again, Natalie nodded.

“And kids are the strongest competition for the attention of the other parent.”

The comment had hung in the air between them then. Dr. Littlefield sat in her chair, hands folded on her lap, waiting for Natalie’s response. But she couldn’t. The words kept repeating in her head: competition for attention. Had the boys been competing for hers, too? Is that why Stephen gave up after Parker left? Her eldest son had wanted his father, but Parker had absolutely no parental attributes.

Those words resonate even now. It was true, Natalie knew. Parker had not cared about the boys from the moment they were born. Though Natalie had tried to reason that he was jealous because they stole her attention, she knew now that it was more than that. Much more.

For the first month after his disappearance, Natalie had continued to contact Parker, left dozens of phone messages about the boys and what they were doing, texted him to arrange some kind of visitation with the kids. Not once did he answer her—or the boys. At first, she was baffled.

The kids didn’t deserve to be abandoned. Then she became indignant, and then she started seeing Dr. Littlefield. It took two years, but she filed for divorce, and she asked her lawyer to ensure she had full custody. She needn’t have bothered. Parker sent a lawyer to the hearing with explicit instructions not to share his contact information. They agreed to everything Natalie requested: custody, the house in Raleigh, as well as the vacation home on the beach, retirement funds, and some stocks.

The Mourning Parade

The Mourning Parade