- Home

- Dawn Reno Langley

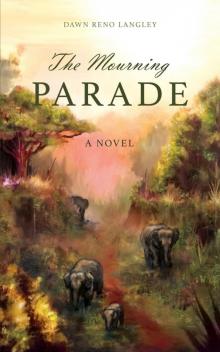

The Mourning Parade

The Mourning Parade Read online

The Mourning

P A R A D E

Dawn Reno Langley

Amberjack Publishing

New York, New York

Amberjack Publishing

228 Park Avenue S #89611

New York, NY 10003-1502

http://amberjackpublishing.com

This book is a work of fiction. Any references to real places are used fictitiously. Names, characters, fictitious places, and events are the products of the author’s imagination, and any resemblance to actual persons, living or dead, places, or events is purely coincidental.

Copyright © 2017 by Dawn Reno Langley

Printed in the United States of America. All rights reserved, including the right to reproduce this book, in part or in whole, in any form whatsoever without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical reviews and certain other noncommercial uses permitted by copyright law.

Publisher’s Cataloging-in-Publication data available upon request.

Cover Design: Red Couch Creative

Artwork: Marco Smouse

One

How had I come to be here

Like them, and overhear

A cry of pain that could have got

loud and worse but hadn’t?

-Elizabeth Bishop

The doorknob felt cold and shimmied almost indiscernibly as the front door lock clicked. A definitive sound. Final. An ending. Natalie placed her right palm against the door and closed her eyes. Breathe, she told herself. Just breathe. Each sip of air required work. Thought. And though air meant life, breathing had become the hardest thing she’d ever done.

She slid the key under the doormat for the realtor who’d arrive after sunrise to put a lock box on the door. When she came home again, this house would no longer be hers. She’d return instead to her townhouse on the beach in Wilmington. This house, her family home, overlooked the Falls Dam, one of the prettiest spots in Wake County. She’d been approached to sell many times, but she’d always refused. She could afford a larger house and modern amenities like a gourmet kitchen or a screening room, but this old farmhouse was home. She knew every creaking floorboard to avoid when she wanted to sneak into the house unnoticed, and how to set the window in the corner bedroom just right so it would stay open to capture the river breeze on a late summer’s night.

Years ago, when her ex-husband, Parker, and she had first seen the house, its view made buying it a no-brainer. It had been the right decision then, but now the house and everything around it appeared different. Her footsteps echoed when she came home late at night. The barn owls the kids loved to imitate had become an irritating noise that kept her from sleeping, and every shifting beam of light made the most mundane items appear sinister. Instead of being a balm for her soul, the view and the house itself only brought up all the memories of the years she spent here with her boys—and Parker. Even the happy memories were unwelcome now.

“You have everything, Miss?” The taxi driver who’d been silently waiting in the driveway startled her. His voice roused a pair of mourning doves nesting in the eaves above where the cabbie stood. They whirred into the sky.

No, I don’t have everything, Natalie wanted to say. I have nothing. But she nodded silently instead.

As the driver maneuvered down the long, winding driveway, Natalie pressed her face against the window and forced herself to count the pine trees lining the road. In an hour or so, the road would be lined with media anxious to ask her how she felt now that a year had passed. She had chosen this early morning flight specifically to ignore such inane questions. Even in the dark quiet of this taxi, she didn’t want to think about how she felt. If she concentrated hard enough, she could stop the scenes that played inside her eyelids like the twitching movements of a silent film. She couldn’t drive when those moments arrived and stole her attention. In fact, it was after one of those blinding memories that she’d finally admitted she needed help.

She’d shared her deepest feelings about life and death with only one person in the past year: Sally Littlefield, her psychiatrist. She’d been too scared to share with anyone else the chilling thoughts she had late at night. The crushing fear that she might be losing her mind, and the realization that maybe being completely insane would be less painful than trying to pretend she could move on, made her lose her perspective. She’d told Dr. Littlefield during the first session that maybe it would be better if she had a complete breakdown. Then maybe she wouldn’t know the guilt of living.

Dr. Littlefield attributed Natalie’s roller-coaster emotions to post-traumatic stress, and she promised the drastic mood swings would eventually subside. Natalie wasn’t so sure.

“It’ll be most difficult for the first year,” Dr. Littlefield had said. “Don’t make any big decisions until you get past that first anniversary. And take care of yourself. Eat. Sleep. Nonstop work isn’t going to make things go away. You have to feel your grief. Embrace it. Cry into your pillow until you have nothing left. Don’t hold back.”

Maman made sure Natalie ate. Too much. Sometimes she discovered two casseroles waiting for her in the refrigerator when she got home from work. Sometimes there was a cheesecake on the front porch. And she always insisted Natalie come over for Sunday dinner. Natalie ate in fits and starts, but she never got into the habit of three square meals a day.

She had listened, but the year was up now, and talking to Dr. Littlefield was no longer enough. Though the doctor didn’t push, she made it clear that the only way to move forward was to put one foot in front of the other. “How?” Natalie would scream. “How the hell do you move on when both of your kids are gone, and you’re still here? Who hates me enough to punish me like this?”

Dr. Littlefield said all the right things after that question. “You’re not being punished. You might never have the answers to everything, but know this: nothing you could’ve said or done would have altered that day. Nothing. Be kind to yourself, Natalie.”

It wasn’t enough. It was never enough. Nothing stopped the pain.

Every time Natalie stepped back into the house, the memories flew at her from every corner of every room like thousands of hummingbirds, moving too quickly to catch, and poking their long beaks into her body, stinging her with images of her kids: Danny hanging off the side of the couch laughing, one tooth missing, upper right side, and beside him, Stephen, eyes crossed, wearing astronaut pajamas. She saw them doing their homework, watching television, baking brownies, making faces when she suggested the garbage needed to be taken out. She heard their voices and laughter so clearly that her heart quickened, and she nearly convinced herself the sound was real. But it wasn’t, and in her heart of hearts, she knew it, so she’d push herself up the stairs past the memory of Danny, barely a year old, learning to walk, and she’d closet herself in her bedroom, door closed against the image of Stephen at seven, dancing down the hallway in his stocking feet. Only in her bedroom were the images stilled, so that’s where she stayed, finally giving in and installing a microwave and coffee maker so she wouldn’t have to go downstairs. She slept and ate there, wishing she found comfort in the house that had been home for so many years, but there was no longer any peace there.

Last night, she’d given in completely to the house and let it swallow her. She stayed awake all night to wallow in the past, opening each door of her heart as she opened every door and drawer in the house. Though her family and staff members at her equine surgery clinic would have helped, packing the memories was something she needed to do alone. She gently stored school photographs, report cards, and Halloween costumes in the last Rubbermaid crate at three in th

e morning, an hour before the taxi was scheduled to arrive.

During that last hour, in the quietest part of the morning, she curled into the couch on her back porch and listened to the night sounds as she stared into the blackness around her. She didn’t need to physically see the pine trees to know they were there, or to trace the ebb and flow of the Neuse River that created her northern property line. She breathed in the scent of their existence, determined to capture the essence of the place where she’d spent the last fifteen years. The longer she sat on the porch, the more she remembered other sounds: the roar of a summer boat filled with teenagers screaming and laughing; the voices of children exploring their way down a woodsy path to the riverbank. An adult’s warning: Be careful. Don’t go too far. The child’s response: Don’t worry, Mommy. I’m right here.

She had seen the taxi’s lights snake down the drive toward the house. Now she watched as the house receded in the rearview mirror. Its rooms would be empty soon. The boxes of items she couldn’t bear to give away or destroy would wait for her at Easy Storage on Route 1 until she returned a year from now. In her suitcases, she had everything she’d need until then.

“So, where are you going?” The driver, a twenty-something, rangy kid wearing a Duke Baseball cap backwards, watched her in the rearview. His green eyes were friendly.

“I’m going to Thailand,” she told him.

“Wow, Thailand. That’s cool. That’s where all those temples are, right?”

She smiled and met the cabbie’s eyes in the mirror again. “Yes, that’s the place. Some of them are even decorated with real rubies and emeralds.” She didn’t know why she chose to tell him that.

His eyes widened. “Maybe someday I’ll get there.”

They drove down I-40 and took the exit to the Raleigh-Durham International Airport without another word. It wasn’t until he’d removed her third suitcase and closed the trunk that he finally asked. “Don’t I know you? You look really familiar.”

Her suitcases stood on the curb in front of the Delta terminal. Through the windows, the terminal was already busy with travelers though the night sky had barely begun to brighten. Her heartbeat quickened as the cabbie stared her down, curious.

“I don’t think we know each other,” she said, grabbing her receipt from his hand and replacing it with a hundred-dollar bill. Too much, she knew, but she would have paid ten times more to get out of the state of North Carolina without being recognized.

“Don’t you want any change?” he asked.

“Keep it.” She signaled to a porter pulling a trolley down the sidewalk. He loaded her three suitcases and headed inside.

Behind her, the cabbie called out, “Hey! I know! I know who you are now. Not too many women with a waist-length, black braid like yours.” He triumphantly grabbed the briefcase she held in her hand, brought her around so they were face-to-face. Her hands started to shake. “You’re the horse doctor who took care of my girl’s mare. Jodi Conchall. Her horse was . . . what the hell was her name? Starfire or Starlite. Something like that. Probably ‘bout ten years ago. Both of them gone now. Horse is dead, Jodi’s just gone. You might not remember.”

She started breathing again. “I remember. Pretty little pinto. Heart problems.” Yes, she remembered. That was the problem. She remembered everything.

A few moments chatting, and she freed herself. Entering the terminal, the harsh lights made her feel exposed. The Delta line was long. Families with bored kids, businessmen in gray suits and sensible loafers, hipsters on their way to someplace more foreign than the next guy. Natalie looked straight ahead, mentally counting the number of people in front of her.

But she couldn’t help noticing the snaking tape that forced all travelers into lines. Her palms sweated. Concentrate, she told herself. Count. Breathe. But her vision swam, and the memory sucked her in.

Standing shoulder-to-shoulder with other parents and siblings, frozen behind the yellow caution tape, waiting. Waiting for the answer to the one-word question: why? Waiting with one beating heart between them and a chorus of soft sniffles and whispered worries floating in the air above them.

Hundreds waited with her for more than an hour at Lakeview Middle School, all standing behind the yellow caution tape, yet she couldn’t hear a sound. No one spoke. Occasionally a moan or a sniffle escaped into the fragile silence, but it was quickly swallowed as if the person—mother, father, grandparent, sister—felt that releasing any grief too early would be traitorous. Bad luck.

After a while, the crowd deepened. Babies cried. Cell phones rang and were answered. Conversations were held in hushed tones.

We don’t know anything yet.

No news.

The police are all over the place, but we don’t know what’s happening.

She’d been trying for a year to forget the eruptions. The cracks that split the air again and again. The gasps. The shrieks. The startled jumps from those in the crowd who stood, united by that yellow tape, as well as by those children in that school. Then the silence. The new and bone-chilling silence. So quiet that when the screams started exploding from the brick building, high-pitched and painful, they were a heavenly blessing. Proof of life.

“Dr. DeAngelo?” The attendant tapped Natalie’s ticket on the counter. Impatient. How many times had she called her name? “Weight is five pounds over on this suitcase. You can either empty something out, or we’ll have to charge you.”

“Go ahead. Charge my card. I need everything I packed. I won’t be back for a year.”

“Doctors without Borders?” The badge on the attendant’s jacket read: Dolores. The name fit.

“No, I’m a veterinarian. I’ll be working at an elephant sanctuary.”

“You can’t get much more exotic than that,” Dolores said as she slapped a ticket onto each suitcase. “I hear they’re pretty smart and protective about their little ones. Strong mothers. My son, he’s five, Alfie’s his name; he loves watching the videos of elephants on YouTube. They’re his favorite animal.”

A stuffed pink elephant, three feet tall. Danny, two years old, sleeping against the elephant’s belly every night.

Natalie swallowed hard. “My sons loved elephants, too,” she managed. “My Danny wanted to free them all.” She wondered if her voice sounded as strained to the attendant as it did to her.

“Be safe over there. They’re always having some kind of revolution.” The attendant handed Natalie her ticket and smiled.

“Exactly what my mother said.” Natalie forced a smile in return, the same kind she wore every day when dealing with her clients. The horses she operated on were like children to their owners. All of them could be reassured with a compassionate smile. That came easily for her, but it also masked her own need for comfort and the reassurance that everything was going to be all right. She used to be pretty confident that she could handle any situation. Now she doubted her own ability to put one foot in front of the other.

Her grief was something she tasted in her mouth first, like the copper overtones of blood when she bit her lip. Then it moved to the back of her throat, threatening to cut off her windpipe. But even when she could breathe again, the grief was still present in the pit of her stomach like a basketball-sized sphere of molten lead. Some days the grief would take the form of a headache. Sometimes it would come as a heart-fluttering anxiety attack, but always—always—it was there. She had gotten used to it by now, and even welcomed the physical pain it put her in, because it felt like the punishment she deserved for being alive, for not speaking lovingly to Stephen that morning, for being overly concerned about being on time instead of giving Danny the extra five minutes he needed to finish eating his breakfast. Instead, he’d eaten it in the car on the way to school. For weeks after he was gone, she refused to clean the crumbs he’d left on the passenger seat.

A man with eyes like a cow’s motioned her through security. She choked b

ack the emotions, reminding herself that she had to breathe. Just follow the people in front of you. She kept her head down at Starbucks, ordering a grande decaf skinny mocha with whipped cream without making eye contact with anyone. She picked up the latest Chris Bohjalian novel at the bookstore, counting the number of pages she had to read before leaving it at the sister store at LAX. No extra weight, she’d promised herself. She kept her head down reading in the waiting area and took her seat on the plane without looking up.

Her seatmates soon arrived. He came down the aisle first: early thirties, trim mustache, dark brown hair that curled around his ears. Brown suede jacket. Loafers. Probably a teacher. He looked at Natalie, then the seat number overhead.

“I’m in there.” He pointed to the window. “Jill, you’re 14E, right? In the middle?” He glanced over his shoulder, then back at Natalie to make sure she was listening, and stared a little harder. He squinted, his brow furrowed, as if he’d left his glasses in his other jacket pocket.

A flurry of activity as he placed his suitcase in the overhead rack and then his partner’s. Jill, a slight woman whose blonde hair was haphazardly gathered atop her head with an orange clip. They squeezed in, all the while apologizing for holding up the line—for making Natalie move—for having too much luggage. Then they were settled.

The two of them nodded at Natalie then looked at each other. Natalie leaned forward on the pretense of watching other passengers board and kept them in her peripheral vision as they whispered, then glanced at her again.

Shit, she thought and lowered her eyes to her book.

They were in the middle of beverage service when Jill leaned over and whispered to Natalie, “We’re from Wake Forest. Our daughter goes to Lakeview Middle School. You’re Dr. DeAngelo, aren’t you?”

She had no choice but to nod. The woman was less than three inches from Natalie’s ear. Her breath smelled of coffee and something fruity that turned Natalie’s stomach.

The Mourning Parade

The Mourning Parade